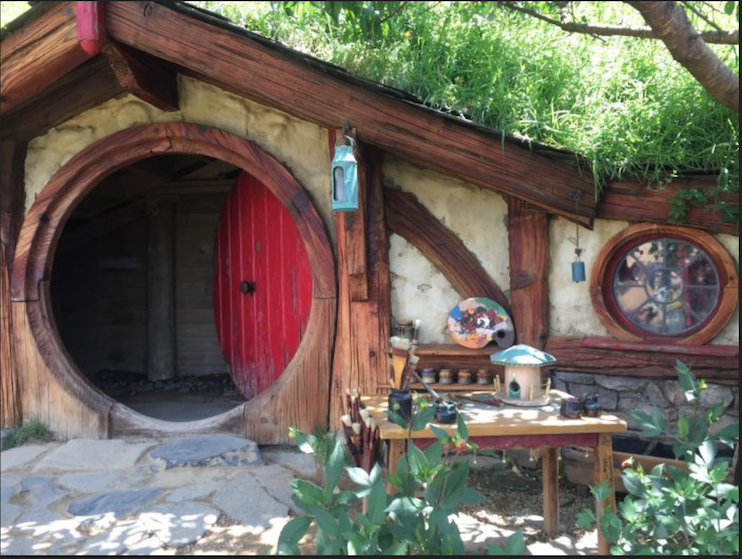

I love the reclaimed depot wood we put on our cabinet ends. The picture doesn’t do it justice.

Leaders, like a builder, can choose to get new employees or work with the old ones. Employees with issues can be seen as disposable—out with the old and in with the new—or as valuable resources worth working toward reclamation.

A Change

I have found a new joy in reclaimed old wood. Old redwood to be precise. Redwood salvaged from a deck that provided the framework for a porch that had deteriorated over time. It surprises me a little bit—this joy of working with tis old wood—because I’ve always been favorably predisposed toward “new.” Maybe it’s my history of allergies. Maybe it’s laziness. But I always enjoyed building with new wood—from scratch if you will—rather than recycling something old . . . and often not being happy with the result. But now that’s all changed.

The destruction phase. If you look closely, you will see our Melodrama sign (to the extreme left) later in our shelving picture on the—mostly—completed porch.

The Wood

It started with a tear-down-and-rebuild project. We live in an old converted train deport. An amazing amalgam of construction. One hundred year old “bones” and newer additions make up the primary building. One of the features we loved was the “four-season porch” on the back. That porch, not in great shape when we bought the property—and poorly built originally—had deteriorated to the point that it needed to be torn off completely or rebuilt. Tear off and rebuilding . . . again not my favorite. But, it had to be done. The next couple of years, with the guidance and assistance of my contractor, consisted of working on weekends on this project, and after finishing the major work with the contractor, I am still working on the finishing touches as I write.

Redwood boards. Planed and ready to use for projects! You can see the discarded metal wagon box in the background. See the redwood wagon below!

The porch was built on top of a redwood deck. Well, it was partially built on a redwood deck. The builders had cobbled together a porch stoop (by the door to the right) and a deck (covering the rest of the porch)—which allowed the whole structure to settle unevenly—there was even a metal stand probing up one part!—and helped the general deterioration. We tore out the whole underlying structure, including the redwood, as part of our rebuild.

Now, if you aren’t into wood, you should know that it is expensive to buy redwood today. When I started building shelving from this wood, I priced new redwood to see how much it would cost to build one of the shelves and found that the wood, alone, would cost me close to $500 to buy new. Now that gets a guy’s attention and makes him look at the reclaimed wood in a totally new light!!

Here are some of the shelves and other Christmas projects—vase stand, and guitar neck rests. Notice the same sign in the background that was in the earlier tear-off picture. No floor yet. Finishing the walls first.

From the salvaged redwood I have built a few sets of shelves, a child’s wagon, a dozen or so guitar head rests (for changing strings), a bunch of guitar picks, one flower-vase frame, and a conductor’s baton case. Mostly these are for gifts, partly for fun. I could show you lots of pictures . . . but I’ll limit myself to one more, that should make the point.

Some of the smaller projects. Mostly the redwood. Some ebony, maple, too.

Leaders and People

All this . . . chaos? . . . effort? . . . history? . . . came to mind recently when a business owner, who was told about our process of helping organizations with their “people issues",” asked, “Why don’t they just fire them?” This sentiment, “just fire them,” sounded eerily like my attitude about wood. Just buy new wood! It’s easier. There are no problems to deal with . . . like there are with old wood. Old wood is too much trouble.

Some leaders see the world in much the same way. They would rather start over with a new employee than struggle to find a solution to their managerial problem. They minimize issues within their culture, system, or leadership that contribute to the problem. The propose superficial fixes and ultimately blame the employee for not changing. These decisions reveal the leader’s true values.

Yes, every leader has to face the fact that sometimes the only choice is to let someone go or do harm to the team or organization. But, as a leader, are you eager to adopt an “out with the old and in with the new” attitude?

I have worked with a few leaders who, a review of history or observation, revealed a pattern of employees passing through a “constant revolving door.” Rarely do these leaders see these decision as driven by their own ego or their behavior and that of the organization as the constant in this pattern. They don’t understand how lies that effect employees and leaders. Communication suffers along the way. They may struggle to see the value of mistakes in creating strong teams. They believe that failure is always bad. Other leaders see value in preserving the value of seasoned employees. They recognize that an investment in these employees may provide a superior long-term benefit.

Yes, working with the “old wood” means you have to engage with the wood in a more rigorous manner . . . trim some damaged wood away. You have to pull nails out of the boards so you don’t ruin a set of planing knives. You will make more cuts to find the solid, usable part of the boards and to reveal the pretty original grain. Finally, you will also have more cut-offs to discard.

Seven Reasons Leaders Should Focus on Retaining Employees

But there are good reasons not to start over with new wood . . . or a new employee.

New wood isn’t the same as old wood. Anyone who has been building for more than 20 years knows that the wood you buy today at the big box stores isn’t the same quality as old wood. Fast-growth, sap-wood, poorly dried, cheap lumber dominate the industry. Old wood has dimensional stability, strong grain, color, hardness, and character.

In most circumstances, employees also gain value over time. They have institutional knowledge, they have experience with the trials and errors of the past. They have awareness of what it was like before the product was available. They have relationships with coworkers, vendors, and customers. Finally, successfully “reclaimed” employees can become the biggest champions of the organization and leadership.

There is a cost . . .to buying new. My father-in-law continues to “whittle-away” at a big block of Desert Ironwood from Mexico that he bought years ago for a little over $100. That one log has been part of projects for more than 20 years. Today, a 3/8" thick, 1.75" wide, 5" large stick will cost $12-15 plus shipping . . . if you can get it at all. A log like my father-in-law’s would run close to $1,000.

Those who study business also talk about the high cost of employee turnover in organizations. The impact on “onboarding,” training, and other “real costs” may be secondary to the impact on the culture, morale, leadership trust, and other “soft factors” that, while critical to success, are less frequently measured. The big problem is, most leaders don’t have an easy cost comparison when deciding if firing an employee is in the best interests of the organization and many minimize the impact on the culture of the team—especially if this is perceived to be a pattern of the management.

The old wood has a unique attractiveness —because it’s old wood. Part of the beauty of working with this old wood is the blemishes . . . the nail-holes, checked areas, and uneven coloring. It leeks “used,” but when the wood is cleaned up, trimmed, planed, sanded, and finished, it is more beautiful that a more “perfect” new board.

“Reclaimed” employees can have this save value. When we do interviews in an organization we typically take a plant tour. We request a guide—an employee who is not a “company ‘Yes!’ person” but who is also not the company critic. When leaders guide us to the right employee for this guidance . . . often someone with a reclamation story about the company . . . other employees’ trust in that individual helps us get very honest information about whatever issues we are seeking. The “stability” of this employee (see below) promotes trust and creates the opportunity for an open dialogue that is priceless to the organization. Other employees see the value in this employee and trust their reliability, know their past history, and see the openness about the organizations past challenges . . . and their faith in the leadership.

Old wood has known attributes where new wood has unknowns. Once again, old wood is far from perfect. But, you do know what you are likely to encounter in working with the wood. That’s worth something. New wood may have a high moisture content and tend to cup, warp, or crack. Old wood, once reclaimed will remain true to form, stable, and increase its value. New wood is an unknown. It may age and become cherished old wood or it may warp, crack, or fail.

As we noted above, a reclaimed employee, in the same way is a “known” commodity. Other employees develop a respect for the employee that has come through challenges to remain a part of the organization. They trust someone who they know has not always “had it together” and see themselves in the real story of that employee. They note the optimism and faith the employee chooses to place in leadership despite the past. A new employee may have those traits, but it is an unknown risk at the time they are hired.

There is a unique satisfaction to reclaiming old wood. Sustainabllity, history, value, reduction of waste, or character and beauty . . . there are many reasons that reclaiming old wood is satisfying. In the same way, there is nothing like developing, challenging, and supporting employees to be their very best . . . and then seeing that benefit the team or organization.

Many leaders are, in fact, very open to the idea of trying to “reclaim” employees. There are several challenges however that can make this fail. This, in itself, could be it’s own post, for our purposes, suffice it to say that a poor understanding of human behavior, a weak commitment to reclamation, a lack of consistent attention over time, fear that it will fail, poor communication or planning . . . these are but a few reasons that it may not succeed without a clearly implemented and monitored plan.

Developing a love of old wood opens up new possibilities. Living in an old Depot was daunting at first. The prospect of reclaiming a structure that had been turned into apartments—with it’s three kitchens and six bathrooms—did not sound like fun. But, tearing out the old porch, finding the redwood, and beginning to use this resource has created possibilities where none existed before. The cabinet ends pictured at the top for example. These boards were, in my estimation, a merely a nuisance, piled up in the attic . . . old, dusty brown boards that I was going to have to deal with at some point. Now, after several layers have been stripped, the boards planed down into quarter inch panels, the rotten parts cut away . . . they are a real center point of our remodel.

In the same way, I have seen leaders that were burned out, dreading coming to work, contemplating leaving their position, who after working through a process of reclamation, were, once again, energized, excited about the next challenge, feeling more optimistic about their role and the organization. As the saying goes, “Success breeds success.”

Working with old wood changes the woodworker. Maybe it’s obvious. The old wood/new wood dichotomy is not new. What has changed is me. Once the woodworker opens him or herself up to using old wood, the world begins to change. Board piles are interesting, seeking out businesses that reclaim wood becomes a passion, helping to tear-down old properties becomes a treasure-field to explore. One sees the cheap woods of modern building. There rekindles a joy in the old, the weathered, the sturdy.

One of the best reasons to be inclined, first, toward reclamation when it comes to employees is that it changes the leader. (A good reason to try and “reclaim” leaders as well! Because they can be more valuable.) No, a desire to focus on reclamation will never preclude firing a bad employee. We have mentioned several times that not all the old wood was kept . . . the bad parts of the board were cut off and discarded . . . the point here is that by taking a positive view toward reclaiming the old many boards can be salvaged, materials have a longer sustainable life, and the leader becomes a more functional, well-rounded, and energized leader.

They put the wagon to immediate use! But it’s not about the wagon, is it? People . . . that’s what it is all about!