Here is the refurbished hydrant! Ready to water the orchard, blueberries, and garden areas. Pre-repair picture below.

Repairing, not replacing, Yard Hydrants

Repair or Replace? On my “to do” list this summer is fixing a couple of frost-free hydrants. To get technical, one is a Woodford Y34 that is starting to leak and the other a Woodford W34 that tends to freeze in the winter (see below). These two hydrants were put in roughly 15 years ago and only now are we having some minor issues. Interestingly, they are not our oldest hydrants. We have three that were already installed when we bought our property, 18 years ago, and which are at least 5 years older. But, the two hydrants with issues that I am repairing are the most used hydrants on the property and perhaps it is this fact that has led to the issues.

Notice, I said “repairing” and not “replacing.” Why? Why am I attempting to repair and not just replace them? Well, not because of aptitude or confidence, in my ability to fix mechanical things, that’s certain. I have never install— or fixed—a hydrant before and, if you are a regular reader of my blog you’ll know, I am not particularly mechanically inclined. But . . . I am cheap . . . and I don’t like the feeling of paying 3-4 times more than it’s worth to have someone else do the work if I think it is possible that I can accomplish it with a little—hopefully not irrational—faith and a willingness to take on small risks.

So, this kind of “new mechanical test of my adequacy” is, admittedly, threatening to my psyche. Fraught with danger . . . I struggle how to approach these tasks and minimize the nagging anxiety of failure hanging over my head. Do I order lots of extra parts to make sure I have the right ones? Resign myself to making multiple trips back and forth to the store? Try and figure out exactly what I need and order only the parts I think I need? Each of these options are laced with potential for feeling like I have failed. Extra parts? Waste of money. Multiple trips? Berating myself for not being smart enough to analyze the needed parts correctly. Exact order? What if I don’t have the right parts and have to delay the repair. Each feels like a failure, looming, like the foreboding outline of a turkey vulture, just waiting for death.

Yes, I know this is part of my irrational expectations for myself—is it too much to ask to just succeed, each, and every time . . . without too much trouble? An irrational product of a brain conditioning over time to fear even minor set backs. My healthier “mind” knows that even people who have good mechanical aptitude may have these issues and even do these same things . . . they just don’t appear to define it as proof of their ineptitude the way my brain does.

But this post is not about repairing my irrational thoughts and beliefs, but about how repairs reveal a leader’s values. (BTW, If you have the same unrelenting standards for yourself, like I do, you might want to do yourself a favor and read what I learned watching a choir make mistakes).

Here is the Woodford parts bag for the repair.

Choices Revealing Values

Lucky for me, that You Tube exists today! You Tube is often my source, or security blanket, for mechanical courage. So, one of my confidence boosting activities, is to watch videos, often times several, of repairs that I am attempting. Seeing the repairs made on the videos makes if much more possible for me to step over the threshold of fear and get started on my own challenges.

But repairing the hydrants reveals something about me and my values . . . here are some of them and, as it relates to leadership, I want to focus on the last one—wanting something that is common.

Yes, I’m cheap. I don’t like “wasting money” that doesn’t have to be spent. So, I am inclined to repair things if possible unless there is a clear advantage to replacement. I know not every one shares this value. Some want “new.” Fine, but I”ll take value, old or new, over “shiny” and “trendy.” Personal preference or value.

I prefer good quality over “new” and often trust that older items have escaped some of the present cheapening of manufacturing that does not make new parts, especially on the cheap end, better than old ones.

I like learning and becoming more mechanically competent . . . even if I’m afraid of “failing.”

I derive a strong sense of success seeing the results of overcoming my fears and items in good working order.

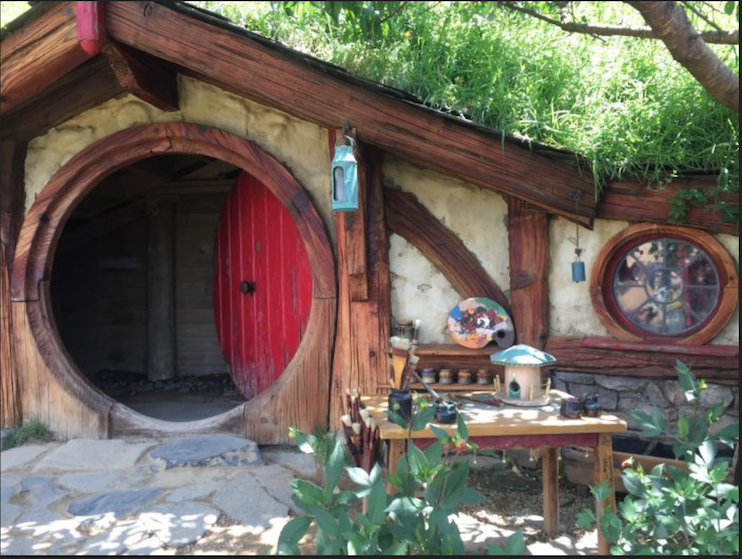

I want a popular quality name brand. I don’t want something that is unique, hard to find, an outlier. This is not true in other areas of my life. I like something different, unique, unusual. But not when it comes to hydrants. I want easy to find parts, An item that won’t be hard to repair or replace. There will be on-line advice on how to operate, fix, or replace. (Seven different You Tube videos so I can find one with the right tools, procedures, etc. that make it “doable”) These are the things I value. So, I have Woodford hydrants—one of the oldest and leading manufacturers of hydrants.. (If I was installing hydrants in a place like Mata Mata, New Zealand, better known as Hobbiton, I wouldn’t want Woodford. But then again, I’d probably be hiring someone else to manufacture and install them!)

Imagine my Woodford hydrant here? It would definitely look modern, out-of-place, and would spoil the magic.

Values and Leading

Recently, someone was telling a business owner about how we help repair human systems in organizations. He struggled to explain to her how we use intensive interviews, focus groups, executive reports, action plans, on-going consulting and coaching . . . to help leaders, teams and employees. Her response? “Why don’t they just fire them?” He retorted, “Sometimes you have an employee so valuable that you want to give them a chance to succeed.”

Now, any of us who have managed large groups of employees know that, regrettably, there are many times where firing someone is the solution that is needed. For me that demarcation line of an employee being “workable” or “not workable” is tied to things like integrity, safety, and honesty. An extreme example will make the point; for most leaders, in most situations, an employee who threatened other employees would be a cause for termination. Stealing, falsification, absences without leave . . . there are plenty of examples. But, most situations, involving people are not this clear.

So, I don’t want to be too hard on this owner. I don’t know what he was thinking . . . maybe it was about a situation most would consider a fire-able offense . . . or what situations he has encountered where repairs were made or were successful.. But I would propose that there are times, many times, when replacement is just not the best option. Let’s consider these from a view point of general principles.

You know that the overall product is good and of high quality. It just needs some upkeep or repair and it will work well for many more years. The cost, in this case, of replacement often exceeds the repair. In business terms, terminating an employee, advertising and recruiting, hiring, on-boarding . . . there are a lot of potential costs to turnover that must be accounted for in the decision. In human terms, what impact does firing someone have on the culture, the motivation, and production of the other employees. For every action there are reactions—positive and negative—that should be considered. There also may be the value of being fair, forgiving, loyal, or other values that make a leader want to factor in past years of good performance.

Replacing sometimes leaves you with an inferior product. Sometimes you just can’t get a good quality replacement or the cost to get the same quality “part” is too high. What do you lose when the experienced employee leaves? What if you can’t get a quality replacement? I recall the impact on an organization who fired a Child Psychiatrist in a rural setting. It was very difficult to find someone to relocate under the circumstances. The organization would up paying for a locum tenens Psychiatrist out of Boston for an extensive period—I’m sure that did not help the bottom line. Similarly, I run a 1948 Ford 8N tractor to do a lot of my shredding/mowing partly because the cost to replace it would be very high.

Replacing a part when the new part undermines the entire system. There is an ancient phrase, “You can’t put a new patch on an old wineskin.” At times a new part is “too much” for the old system. Often organizations bring in a new leader because of problems but if nothing has been done to deal with the underlying issues, these new leaders often either fail to make significant process or are “run off” Then the organization or team is often labelled as “toxic” and failure becomes an expected “explanatory fiction” of the “way it is” making transformative change extremely unlikely.

Replacing a part when it’s role is more than just it’s functional value. I mentioned the Ford 8N tractor earlier. The truth is, it is more than just a tool. It is my father-in-law’s tractor, passed down to his daughter, and an item around which many family memories have been made and core family values have been reinforced. That farm-born independence, hard-working, care for your equipment, cherished memories of past accomplishments . . . Maybe, someday, this tractor will pass out of our family’s ownership, but I don’t see it happening for the next generation or two for sure.

As a leader, conveying a belief that 1. your employees at their core possess good qualities, 2. that replacing them will not automatically lead to a better product, 3. that the system will react tot the seismic shift as an employee leaves, and 4. that employees and their relationships within the organization are not just a transactional exchange of function and remuneration can go along way to creating a valued culture where high performance can be built. It is not the “be all or end all” but it’s a good start.

Repair or replace? What ever you as a leader decide it will express your values and may define how you are perceived as a leader. Keeping a defective hydrant is frustrating, and discouraging to those interacting with it, and it may lead to more damage of the system. It needs to be replaced. But sometimes, really understanding the problem, taking it apart, and replacing the deteriorated bushing, refreshing the old hardened rubber with new, and a little paint gives you something more valuable, and less costly, that buying new.

Here’s my close up before the repair . . . so I can remember how the handle linkage goes together!